Drive-In Roulette was played as the main feature for the Carlisle Carport Cinema project in May 2020.

Filmed from a fixed point looking directly through the front windscreen of my car, Drive In Roulette (2020), a fifteen-minute video, captured the repetitive driving in and out of other peoples’ driveways and carports in the South-East Perth suburbs of Carlisle, Kewdale, Belmont, Cloverdale, Burswood and Victoria Park.

Drive-In Roulette consisted of driving into someone else’s driveway, idling for twenty seconds before reversing back onto the street. The video revealed the carport as a private place despite it being visible and accessible from the street. Each carport provided a different experience determined by its immediate built and landscape environment. For example, some carports were fully bricked-in, creating a constrictive and dark atmosphere, wherein comparison, open carports with a view of the garden felt expansive and calm. With each varying carport, the video shared my experiences of unease and fear, humour and serenity as I sat uninvited in up to twenty different carports. Looking through a physical and virtual windscreen, I had generated an ironic viewing experience that uncovered a range of dynamics between public and private space including suggestions of hospitality and defence, humour and drama within the ordinariness of the humble driveway and carport.

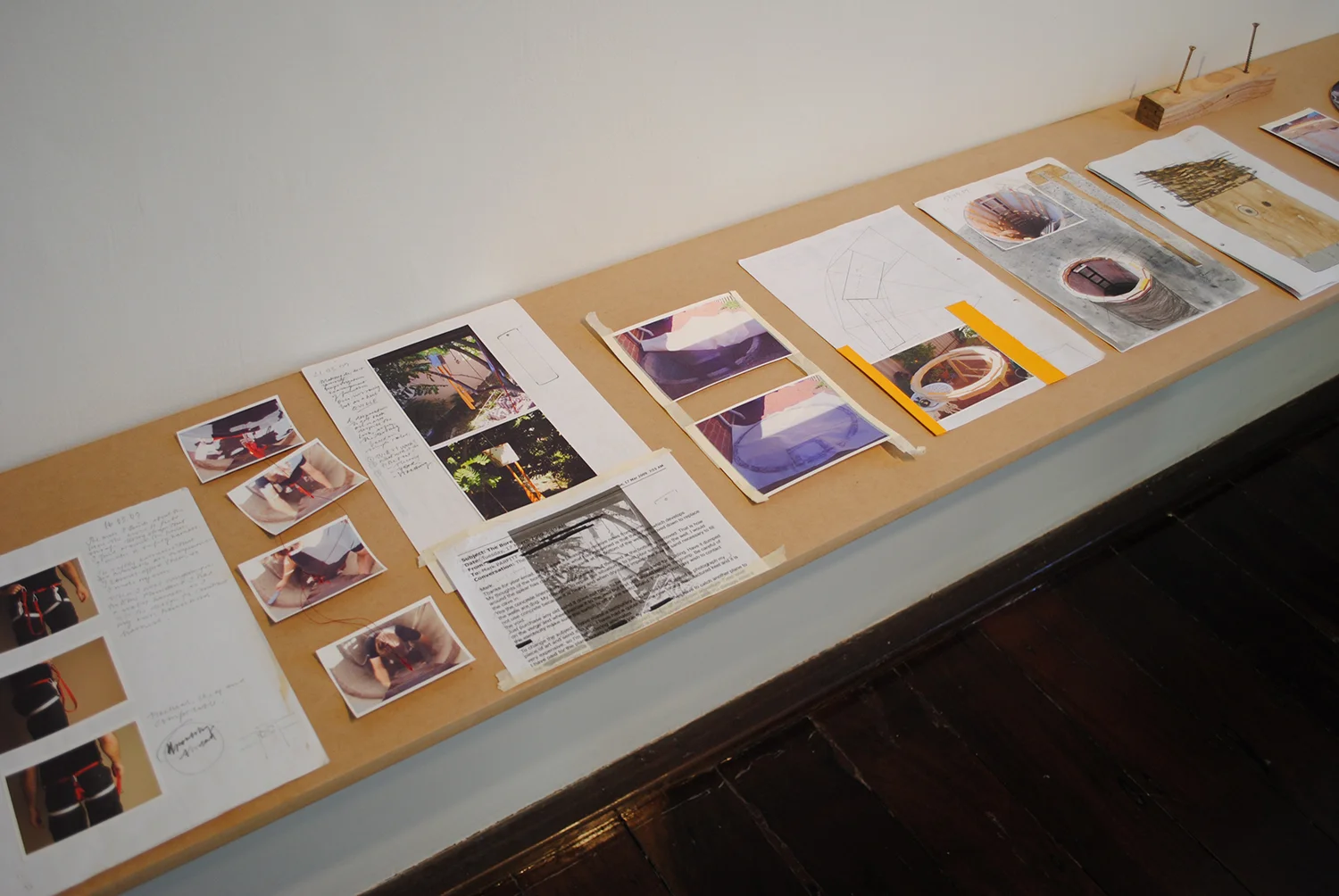

The design of Drive-In Roulette began by going beyond my own carport and producing a new artwork using multiple sites. Though I planned to park in others’ carports, I set some parameters, driving as close to home as possible to maintain the representation of the area in which I lived. The idea was to start from my own suburb of Carlisle and work my way out to other adjoining South-East Perth suburbs of Kewdale, Belmont, Cloverdale, Burswood and Victoria Park. In order to capture the action, I built a camera rig inside the car that spanned across the two front seats with the camera positioned in the centre at a fixed point looking directly through the front windscreen. As I drove through the suburbs, I set myself the choice that I could either turn left or right, seizing upon a chance moment to drive into someone else’s carport. For over a week I had gathered up to forty carport visits and recorded hours of driving in the streets of neighbouring suburbs. Though the title of the work Drive-In Roulette suggests a random method, I still employed some level of discernment driving through the streets. The carport had to be empty as if parking in one’s own carport. This was important for the audience since the aim was to overlap the virtual experience of driving into other carports with the experience of driving into my carport for the anticipated Carlisle Carport Cinema (2020). Once I committed to turning, I drove as far as I could into the carport and remained parked for twenty seconds. This would allow time for the audience to notice the character and nature of the carport. Inadvertently the pause also created a strong sense of tension. For the audience and artist, it was awkward to be parked in another’s carport since I was not meant to be there. It became important to generate an artwork that challenged the neutrality of the carport and reveal an aesthetic, social or political agenda that may lay hidden in plain sight. In order to draw attention to the carport as a site, almost all footage of driving in the streets was removed; leaving just the carport entries, occupation and exits. The result was a rhythmic sequence of carport encounters that concentrated the experience and created a pattern of carport comparisons. I realised that Drive-In Roulette in order to be a site-specific artwork was not necessarily bound to the exact location of my own carport. The site had extended to multiple locations while the viewer experience had moved from a physical place (ie. phenomenological/experiential paradigm of site-specificity) to a virtual setting through the medium of video.

By repetitively sequencing comparisons of carports as well as controlling the amount of time spent in each carport, the perceptual and spatial experience of a site gave way to emerging conversations with my audience about the social, cultural and political nature of the humble carport. Through these conversations Drive-In Roulette aligned with Miwon Kwon’s third definition of site specificity that a site is not necessarily physical and can be a “discursive” place, an expanded concept of site specificity that functions across multiple locations within everyday places. The idea of site extends to documentary, textual and internet spaces that accommodate an interchange of ideas and discussion that are about the site. The physicality of site remains as part of the definition; however, site-specific artworks generate meaning from themes, issues and debates that exist within the social and cultural context of a site (Kwon 2002, 26). On many occasions, the artworks are temporal and operate as an activity, gesture or event within the site. Kwon says, “the distinguishing characteristic of today’s site-orientated art is the way in which the artwork’s relationship to the actuality of a location (as site) and the social conditions of the institutional frame (as site) are both subordinate to a discursively determined site that is delineated as a field of knowledge, intellectual exchange, or cultural debate” (Kwon 2002, 26). Understood as a discursive place, Drive-In Roulette generated conversations about staging scenes in domestic environments, the private and public nature of the front yard, with the house as alternative location to the art gallery.

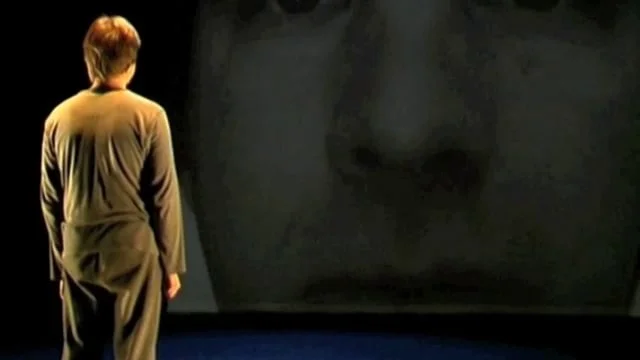

Drive-In Roulette (2020) aligns with artworks produced by American artist Lee Walton who creates video artworks that bring attention to and create an appreciation for unspectacular situations in the context of his daily life. Amongst a multitude of actions such as selling a car, wishing people happy birthday, playing basketball and hiding behind things in suburban settings, Walton elevates habitual social and cultural gestures to a critical level through strategies of chance, gameplay and participation. Similarly, the gesture of parking in carports for Drive-In Roulette (2020), Walton’s videos provide an immediacy to the realities of everyday seen through a repetitive action that is played out in the public realm using a practical approach to video documentation. For example, in the video artwork The Competitionist (2010), Walton repetitively performs a sixty-metre sprint at a local Olympic style athletics track, chasing down joggers who are merely doing casual laps. Walton judges his start and chases down his unsuspecting competitor who unknowingly has been granted a handicap all the way for an exciting photo finish. The video is precisely edited so we see Walton performing the sprint over and over again, competing with a different runner each time. By concentrating on the win, Walton transforms himself from average athlete to a champion every time using humour by adding phony audio of cheers celebrating his unspectacular and suspect victories. By repeating the gesture of the chase, Walton reveals that even in an ordinary setting, no matter the level of athleticism, there is a competitor within. Commonly repeating the same gesture in each video, Walton continuously tests the characteristics of his subject matter revealing or uncovering something that is unconscious or ignored in a thoughtful and humorous way. Walton explains, “As a practice, I hope my work can remind us what is real. To do this, I draw attention to the seemingly unspectacular. My art practice highlights the routine and habitual to rediscover the things we’re forgotten how to see. I am invested in art as a daily practice that can heighten one’s awareness, a reminder to appreciate the aesthetics of everyday moments” (Walton 2020).

Similar to artist Lee Walton, I also consider that concentrating on the unspectacular activities within a site can challenge everyday places, particularly the house, to create artworks that surpass the ordinariness of place. Like Walton, I staged scenes in Drive-In Roulette (2020) to reveal social sensitivities discovered in other people’s carports when crossing the threshold between public and private space. In some carport encounters, I felt welcome, such as when I drove into an open carport that featured a succulent plant sitting on a chair against the side wall. I felt like an expected visitor who had received permission from the householder to come over and pick it up. In other situations, there was a sense of hostility for example, one carport displayed a sign ‘BEWARE OF DOGS THEY BITE’ near a side gate. The house felt abandoned, in need of repair with an overgrown garden. The front yard held the potential for a surprised householder to come out and chase me out of the driveway. To increase the dynamic of feeling unwelcome, I staged scenes enlisting friends to act as home occupants emerging from their houses or standing in their carport staring directly back at the camera located next to me in the car. Though no one came out when parked in strangers’ carports, I created the scenes in response to a sense of fear that a home occupier could come out at any moment and question why I was there.

Due to these excursions into other peoples’ spaces I understand, to go beyond the normal expectations of place, an extraordinary action is required within it. In comparison to American artist Lee Walton’s body of works, I considered Drive in Roulette a successful artwork due to isolating the carport as a site for intense scrutiny and similar to Walton, elevating the action of parking as a staged and excessive performance. A transformation occurred whereby my daily experience of my domestic environment changed from a passive transience of space to an active and creative engagement within the place I lived. Drive-In Roulette enabled a re-thinking beyond my house as a place where I merely lived out my daily life. I understand that it is possible to elevate my lived experience from my own house and discover a range of social and cultural dynamics between public and private space including hospitality and defence, humour and drama within the ordinariness of the humble carport. For example, the social dynamics of the carport in Drive-In Roulette can be understood through Peter Timms’ description of the Australian suburban front yard in his chapter From Stage Set to Peep Show in his book Australia’s Quarter Acre (2006). Timms describes the front yard and garden, including the driveway and carport as a half-private, half-public space. Tracing back to the early 20th Century, Timms says that the Australian front garden used to be more about displaying an orderly garden on full display that was welcoming and open to the public. It visualised that there was nothing to hide. In recent times however, with the advent of higher fences and close circuit television cameras (CCTV) coming into use, the front yard has become increasingly private. Timms writes, “Given the suburban front garden is a display space that people hide behind, like a mask, we can never be quite sure whether what it is telling us is the truth or artifice. It sends mixed messages, which can cause uneasiness” (Timms 2006, 71). Through the experience of driving into other’s front yards, I realised that Drive-In Roulette, not only crossed a line between public and private space, but also scrutinised how fellow neighbours presented themselves to the greater suburban community. Conversely, Drive-In Roulette enabled me to consider how I present myself to the community using my house especially my front yard for future site-specific artworks. My domestic environment remains a display space however, rather than hiding within, site-specific artworks allow the occupant to emerge from everyday living to reveal themselves to their community.

References

Timms, P. 2006. Australia’s Quarter Acre: The Story of the Ordinary Suburban Garden. Melbourne. The Miegunyah Press.

Walton, L. “The Competitionist.” Accessed January 24, 2021. http://www.leewalton.com/art/the-competitionist/